Today's guest contributor is Carol Edwards. After many years as a youth services librarian, Carol currently works as the Project Coordinator for SPELL; Supporting Parents in Early Literacy through Libraries. She has a granddaughter just starting first grade who is a real reader and has been reminding her of the way learning to read is both a challenge and very rewarding. Carol has served on the Newbery, Caldecott, Morris, and Coretta Scott King Award committees as well as being involved in CLEL, Colorado Libraries for Early Literacy and their CLEL BELL Awards.

The classic books for early readers that are still around exemplify the needs of beginning readers. These readers struggle to look at the black ink marks on the page and turn those into first words, then ideas and stories in their heads.

I’ve looked back at a number of titles that charmed and delighted those just learning to read long before the Geisel Award was instituted in 2006. While Dr. Seuss is the obvious name to mention, I thought I would not focus on his work this time, but on others who were, I think, just as influential in developing the standards that have been handed down.

One thing is clear. The subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read and the story move along quickly. A Kiss for Little Bear by Else Holmelund Minarik (1968) is a favorite. Things happen from page to page, and always the pictures provide clues to the decoding required. I just love the memorable phrases, such as "Too much kissing" [p.21]. A satisfying story with a beginning, middle and end.

Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books are classics that everyone knows. Frog and Toad are good friends, and the books about them evoke many of the best qualities of early readers today. Frog and Toad are both not nearly as clever as the average kid learning to read. Doesn't this remind you of Gerald and Piggie? This ability for the reader to feel superior and to laugh at their antics is a quality that Lobel showcased in Owl at Home (1975) as well. There are places in them to pause and consider the motivation and thoughts of the characters. This allows the reader to both focus on what is being read and to consider it at a slow pace that is commensurate with their reading ability. Since these books are often read with a better reader nearby, whether grownup or older child, the humor is bound to connect the two readers, making the reading seem cooperative rather than competitive.

Helen Palmer, who wrote A Fish out of Water, was married to Ted Geisel until her death in 1967, and adapted this book from a short story of his. The lovely repetition and the increasingly unbelievable results are reminiscent of other Dr. Seuss titles, but this book has its own charm as the conclusion returns the reader to normalcy. The flow between pictures and words works very well, providing cues and laughter simultaneously. Personally, this story always resonated with me, as I have distinct memories of being told not to feed the fish too much fish food. There are probably many kids who have wondered what would happen, although the fish usually die as mine did. A sad ending deftly avoided here.

Robert Lopshire wrote Put Me in the Zoo (1960), and it's certainly showing its age, particularly in the illustrations. However it continues to serve young readers. Not full of plot, but an engaging stroll with a strange creature sharing his odd powers. He speaks directly to both a young girl and boy, and to the reader. It's an early example of how engaging the reader as a participant can pay off.

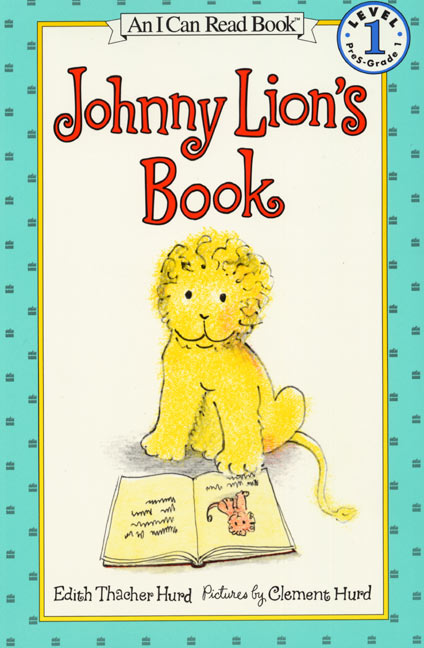

Johnny Lion's Book (1965) shows the reader how the story in a book can be as exciting as doing those things in the real world, but not nearly as dangerous. Johnny's good behavior is rewarded by being able to stay up "very, very late." p.59. A reward indeed -- as every book you read should be.

Classic early readers show us that repetition and simple vocabulary are not all that is needed. We need stories that are appealing, that both move along quickly and allow the reader time to absorb the meaning of the words. Illustrations play a key role, and there is obviously no one right way to do it, but a light touch is certainly appreciated.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.