|

| Book cover of We Are All Me by Jordan Crane |

The story (or is it a poem?) starts with the self then expands into body, world, air, cloud, water. Earth. Seed. Sunshine. Root. Life grows into leaves and fruits and bugs and bees. But, under it all is bone, meat, a heartbeat. Cells. Atoms. Existence. The message that’s preached: “We are all one.”

|

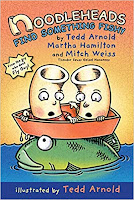

| Image from Toon-Books.com |

I know what you’re thinking. This sounds like a trippy book. It is a trippy book, hands down. But it’s also kind of amazing. And I’ve never seen anything like it in an early reader. Of the 96 words I mentioned, 44 unique words are used. About a third of those are sight words. The book relies on repetition of both words and images to help convey meaning as it shifts into more complex words like “aware” or “exists” or “atom.”

This rhythmic repetition carries the story—and the reader—along. Likewise, the way the pictures build on (and connect to) each other is integral to understanding the book. For instance, the clouds that are introduced on one page (on which the text reads “made of air”) are replicated on the next (“and of cloud”) but then changed to indicate rain (“made of water”). For something about interconnectedness, it’s a very granular presentation. The pictures bring the complexity of the theme into something easier to decode for a K-2nd grade audience.

|

| Image from Toon-Books.com |

Sure, it’s an abstract book. It’s an abstract concept, too. But as far as simplified philosophy goes, it doesn’t get much better than this. Though I think the chances that the Geisel committee will choose this one are slim to none, I’m still holding out some hope. I’m a big fan of anything that pushes the limits of the format and I think this title does just that.