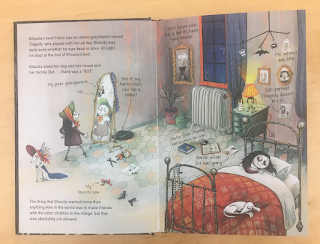

When Charlie & Mouse won Geisel gold, it was thrilling

for many reasons. One of these was the inclusion of the neighbors Mr. Michael

and Mr. Eric, bringing some librarians to tears. Mr. Michael and Mr. Eric,

based on two of Laurel Snyder’s actual neighbors, appear in just one of the

stories included in Charlie & Mouse, and then only briefly. But they are

notable as the first depiction of a same-sex couple in any beginning reader

title (or as some might point out, the

first canonical, human same-sex couple).

Despite their very brief appearance, at least

one reviewer found their presence objectionable, calling out their presence and

Mouse’s choice to wear a tutu, headband, and cowboy boots in another of the

stories as evidence of a “LGBTQ agenda”. Author Laurel Snyder took the

criticism in stride, tweeting “MWAHAHAHAHA! I am coming for your children with

my insidious “all children deserve to feel like people” agenda”.

All children deserve to feel like people. They deserve to

see themselves, their families, and their communities depicted in the books

they read. Children who are transgender, or gender creative, or who have gay

parents, or gay grandparents – they all deserve to see their experience

reflected in books, including the books they are learning to read. Books for

beginning readers have lagged behind other books – including board books – when it comes to

incorporating diverse characters and experiences. With regards to LGBTQIA+

representation, we can speculate as to why this gap exists. With the picture

books “And Tango Makes Three” and “I am Jazz” taking a place among the top 10 most challenged

books of 2017 is it any wonder that publishers might play it safe with

regards to any potential “LGBT content” in a format that relies heavily on marketability to schools?

And yet, all children deserve to feel like people.

Including, and especially, those just learning to read. There’s room on our

shelves for so many more types of readers to see themselves reflected at every

age and stage of learning to read. With love and appreciation to Laurel Snyder

and Emily Hughes for introducing us to Mr. Michael and Mr. Eric, and for Mouse’s tutu – I hope

that they are just the beginning. We need everyday LGBTQIA+ representation in beginning readers.