Hi, Geisel Guessers! I hope many of you are looking forward to a relaxing weekend, but please take a minute right now to answer this three-question survey about how beginning reader books are shelved and leveled in your library. Feel free to answer this survey even if you're not the one making these decisions (for instance, if you are a library patron, you can describe how the library you use shelves these books). If you're a teacher, you can answer for your classroom library, or the library in your school, or the public library you visit most often. We'll be back next week with a post about the results we get, so encourage your friends and colleagues to participate, as well!

Create your own user feedback survey

Pages

▼

Friday, August 30, 2019

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

Harold & Hog Pretend For Real! by Dan Santat

|

| photo credit to Nikko Custodio |

|

| Harold & Hog Pretend for Real! by Dan Santat cover |

Could Harold and Hog Pretend for Real earn Geisel recognition? Sure, obviously it could. It has all the hallmarks of a winner or honor: Clear, easy to parse design, concise storytelling, controlled vocabulary with lots of repetition, illustrations that support the reader as they decode, humor, and stakes that rise with each page turn, propelling the story to its satisfying conclusion. As a meta-satirical “Elephant and Piggie” title, it’s a textbook example of what’s won in the past: Willems’ "Elephant and Piggie" titles have taken two golden Geisel medals and five honors (not counting the Elephant and Piggie Like Reading titles, as they have different authors/illustrators.)

The 2017 gold medal went to "Elephant and Piggie Like Reading" title We Are Growing by Laurie Keller, which coincidentally shared a release date with The Cookie Fiasco, the only other series entry (to date) penned by Santat and Willems. So there’s precedent for both “Elephant and Piggie” books and for “Elephant and Piggie Like Reading” books to earn Geisel citations. Perhaps it’s also worth noting that Willems’ We Are in a Book, a 2010 Geisel honor, is, like this title, one that stretches the confines of what we expect an easy reader to be and do in terms of storytelling and self-reference.

But whereas We Are in a Book breaks the 4th wall, this book knocks down that wall, replaces it with a mirror, and then sets up another mirror opposite the first, creating a delightful and recursive callback cycle that loops ad infinitum.

Whoa.

Finally, consider the Geisel criteria “demonstrate creativity and imagination to engage children in reading” Huh. Wait—if the premise of this story is Gerald and Piggie reading a book about Harold and Hog pretending to be Gerald and Piggie...doesn’t that mean Harold and Hog Pretend for Real is literally simultaneously about and demonstrating creativity and imagination to engage the book’s reader? I mean, what even is pretending if not creativity and imagination?!

Ouch. I think I broke my brain.

Monday, August 26, 2019

Hey, Water! by Antoinette Portis

|

Photo of Betsy Bird.

Courtesy of Betsy Bird.

|

|

Hey, Water! by Antoinette Portis

book cover

|

Until now?

Hey, Water! by Antoinette Portis begins with our guide, a brown-skinned girl named Zoe, calling out, “Hey, water! I know you! You’re all around.” She proceeds to list all the different ways you can encounter this essential resource. It’s in your home. In large bodies of water. In a teardrop falling from your eye. There’s steam and fog, snowmen and fish, even your own body! What’s the best thing to say after all of that? “Hey, water, thank you!”

Now I’m coming at this book from a children’s librarian standpoint, and you know what we children’s librarians love? New STEM related books for our thematic storytimes! That’s part of the joy of this book. For the kids just learning to read there are short sentences peppered throughout. For the youngest squirmy types, each image shows a single simple word for them to see and comprehend. Tackling big ideas (like the water cycle) with simple words and images is one of the hardest jobs to do in this business. Oh, and did I mention it’s gorgeous? The Geisel Award terms and criteria state that the awards go to creators that, “through their literary and artistic achievements, demonstrate creativity and imagination to engage children in reading.” Not much more is said about those “artistic achievements” but as they are alluded to, I’d like to recommend that folks take them into consideration.

|

| Image of child running through the sprinklers on the left. On the right, a child standing in the shower. |

It’s not perfect, of course. For example, at one point the book likens an iceberg to a rock, joking that it’s a rock that can float, or a rock you can skate on. I could see some scientifically minded gatekeepers not caring much for that, saying that it misleads children into thinking that ice and rocks are one and the same. Another concern involves the repetition of words. The Geisel Award criteria is fairly clear that, “Words should be repeated to ensure knowledge retention.” The book is almost too simple to repeat many words, though I did notice that “water” does crop up from time to time.

|

| Image on left of a teapot steaming on the stove. On the right, three birds flying below a cloud. |

The Geisel Award criteria does not preclude nonfiction, nor does it encourage it. As with all things, it is up to the discretion of the committee itself to determine whether or not a book meets with its standards. Even so, I can hope that a book this joyous in its willingness to teach, not just language skills, but science as well, will earn the respect of all gatekeepers. Fun, funny, and desperately smart, this is a book to keep your eye on.

Friday, August 23, 2019

Charlie and Mouse Even Better by Laurel Snyder, illustrated by Emily Hughes

Our guest blogger today is Taylor Worley. Taylor (she/her) is a Youth Librarian at Springfield Public Library in Oregon. When she isn’t reading, she can be found drinking tea while stuck in a video game, making something with yarn, or exploring. She has two dogs, Olivander (Oliver) and Gregorovitch (Gregory). You can find her on Instagram or Goodreads @thatonelibrarian.

Our guest blogger today is Taylor Worley. Taylor (she/her) is a Youth Librarian at Springfield Public Library in Oregon. When she isn’t reading, she can be found drinking tea while stuck in a video game, making something with yarn, or exploring. She has two dogs, Olivander (Oliver) and Gregorovitch (Gregory). You can find her on Instagram or Goodreads @thatonelibrarian.

Charlie and Mouse are back for round three! These two adorable kids leapt onto the early reader scene in 2017 with their debut, Charlie and Mouse. Author Laurel Snyder and illustrator Emily Hughes took home the Geisel Award for that first book in 2018. Since then, readers got to know Charlie and Mouse more in Charlie and Mouse and Grumpy and now in Charlie and Mouse Even Better. Even Better is eligible for the 2020 Geisel Award, but does the third outing stand up to the legacy of the first?

Even Better is divided into four short chapters: making pancakes with Mom, gift shopping with Dad, birthday party prep and disaster, and operation “distract mom”/successful birthday celebration. This format, accompanied by Hughes’ distinct illustrations, is consistent throughout the series and is a large part of what makes the titles successful for beginning readers. The chapters are not numbered; they are simply headings that provide a key for the plot’s shifting focus. The text stays tight and straightforward with wide margins and ample line spacing. The illustrations are the epitome of sweet, with bright colors and feathery lines. Commendation must be given to Hughes for her ability to express a vast array of emotions through eyebrows alone!

With the history of the series, there is no denying that Charlie and Mouse are a great resource for beginning readers. The question here, however, is if Even Better reaches that benchmark of “distinguished” above all other beginning reader titles this year. When reading Even Better to a variety of willing participants, one thing particularly caught my attention. My youngest listeners - those entering Kindergarten in fall 2019 - very much enjoyed this title as a read-aloud. They engaged with the pictures, asked questions, and wanted to continue through each page until the end. However, an even slightly older audience quickly lost interest in this title. When surveying families, those with incoming first and second graders unanimously said, “No, my child wouldn’t be drawn to this book.” So, where is the disconnect?

Charlie and Mouse are young characters, and the cover of Even Better looks, in my sample audiences’ words, “babyish”. The text, however, is more challenging. The disconnect, I believe, is in the presentation of this particular title versus its intended audience. The intended audience is just a touch older than the audience that is enjoying this title as a read-aloud. Consequently, this book struggles to find the sweet spot of “motivating independent reading” while maintaining the “page-turning dynamic.” This doesn’t mean it is a bad book by any stretch, but it does undermine the book’s ability to take home a Geisel for being the “most distinguished” beginning reader title this year.

The TLDR is that Charlie and Mouse Even Better is another warm, fuzzy, and lovely entry in the Charlie and Mouse series. It is a good resource for some, but perhaps not all, beginning readers. It should absolutely be in your libraries, but I would be surprised if it walked away with the gold this year.

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

Circle by Mac Barnett, Illustrated by Jon Klassen

|

Head shot of Ellysa Stern Cahoy.

Courtesy of Ellysa Stern Cahoy.

|

Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen (2012 Geisel Honor for I Want My Hat Back) are back with the final entry in their Shape Trilogy, focused on the misadventures of geometrically shaped friends. Circle follows Square and Triangle, and the book is similar to the other titles in this triumvirate in design and plot structure.

|

Circle by Mac Barnett,

illustrated by Jon Klassen

book cover

|

|

| Image of Circle, Square, and Triangle look at Circle's waterfall from Circle by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen |

Each of the Shape Trilogy books feature a cardboard cover with rounded edges, with the cover featuring the shape at the center of each book. The design is very artistic and spare, placing the focus on the illustrations, created digitally and with watercolor and graphite. The page layout is very clean and simple, and the New Century Schoolbook font is one used in many easy reader texts. There is ample white space and the text is placed in accompaniment to illustrations in a manner that is easily navigable to readers. At 42 pages, the book more than meets the minimum number of pages required for Geisel consideration. The sentences are simple, straightforward, and repeat words, such as ‘waterfall’, ‘dark’, ‘rules’, and ‘farther’. The illustrations are evocative (including those picturing the darkness behind the waterfall) and match the plot, which is well paced and encourages the reader to finish the book. The innovative design, creative illustrations, and unique plot combine to create a successful experience for the reader.

|

| Image of Circle searching the darkness for Triangle from Circle by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen |

Will Circle make the Geisel Award list for 2020? It is perhaps telling that Circle’s predecessors, Triangle and Square, have not been recognized by prior Geisel Award Committees. While the books in this series are highly original, they are also very quirky. Each book (Circle included) ends with an existential question (in Circle, it is directed at the mysterious shape encountered in the darkness behind the waterfall, asking the reader, “If you close your eyes, what shape do you picture?” The brief, episodic plot and ending philosophical question makes Circle (and the earlier titles) feel slight. Circle’s darkness encounter behind the waterfall involves mistaken identity, and may be confusing to some. While the Shape Trilogy titles are beautiful, highly creative, and well constructed easy readers, they are perhaps not books that a young reader would want to hear more than once.

What are your thoughts? Do you think that Circle will be the shape that gains Geisel attention?

Monday, August 19, 2019

How to Do Nonfiction for Emerging Readers (And How Not To...)

Ashley Waring is a Children's Librarian at the Reading Public Library (MA). She loves informational books, because learning something new is awesome!

Ashley Waring is a Children's Librarian at the Reading Public Library (MA). She loves informational books, because learning something new is awesome!Young children are curious about the world around them, and a well-written nonfiction book can provide information and excitement. The Sibert Award celebrates the best informational books for young readers, ages birth to 14. While Sibert-winning titles are by definition exceptional nonfiction books, they are not necessarily successful at supporting a child who is learning to read. A Geisel-winning nonfiction book will not only inform the child, but will support and encourage her beginning reading experiences. According to past Geisel committees, finding a nonfiction book that can do this is rare – only 3 nonfiction books have won Geisel honors since the award was first given in 2006.

|

| Vulture View by April Pulley Sayre, illustrated by Steve Jenkins 2008 Geisel Honor Winner |

|

| Hello, Bumblebee Bat by Darrin Lunde, illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne 2008 Geisel Honor Winner |

|

| Wolfsnail by Sarah C. Campbell, photographs by Sarah C. Campbell and Richard P. Campbell 2009 Geisel Honor Winner |

|

| Interior from Vulture View |

|

| Interior from Hello, Bumblebee Bat |

Hello, Bumblebee Bat has less of a narrative structure, but facts are presented with a repeated call and response structure, making it more accessible and engaging. Every page begins with a question, for example, “Bumblebee Bat, how small are you?” The answer is presented in short, simple sentences without complicated vocabulary, while gentle and realistic illustrations support the reader. An example of the success of this nonfiction book is the explanation of echolocation on pages 9-10. The illustrations include other familiar animals that help to give a sense of scale.

|

| Interior from Wolfsnail |

All three titles are about animals, a perennial favorite topic for children, and a fit for the Geisel criteria: “The subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read.” By having strong narratives, supportive illustrations, straight-forward sentences, and uncluttered design, all of these books meet Geisel criteria while also being informative books for beginning readers.

Friday, August 16, 2019

Look Out! A Storm! and Poof! A Bot! by David Milgrim

| |

| Stacey Rattner |

I made an appointment to meet with my friend, Natalia. She was spinning around when she greeted me at the door. Her parents assured me that she was ready to read but warned she might be a little rusty. "No problem," I said as I handed the rising first grader Look Out! A Storm! and Poof! A Bot! both by Geisel honor winning author and illustrator, David Milgrim.

| ||

| Image courtesy of the author. Used with permission. |

Olly the rhinoceros is in a bad mood. His friend Otto doesn't know it until he greets him with a big "HI!" (Natalia had fun shouting that!). Oh no! Olly starts chasing Otto right into Flip and Flop. And NOW Flip and Flop are chasing Otto who is running after Olly until...a storm comes. Everyone hops on Olly's back to find cover. They wait the storm out and everyone, including Olly, is now in a good mood.

Natalia needed help with only a few words. The names "Olly" and "Flip" were a challenge at first. She struggled with "storm" but after I encouraged her to use the illustrations as clues, she figured it out. "Now" was difficult but she knew "know" so we had a nice discussion about the differences in those words.

| |

| Look Out! A Storm! by David Milgrim |

The book teleported me back to 1975 and Mrs. Marcus when I read the repetitiveness of "See Olly go. See Otto go." However, this book is so much more exciting than Dick and Jane ever were. Natalia is proof: "I liked that the storm was cool. I didn't like the chasing part because Olly has a sharp horn and I'm afraid he's going to hurt Otto."

Poof! A Bot! is categorized as a "Ready-to-Go!" reader, one level easier than Look Out! A Storm! The opening pages include all the words in the story. Natalia sped through most of them. The bonus words were, well, rightly labeled "bonus" (ie, eye, mint, pie, tea) but by giving her a preview ahead of time, Natalia was more successful when she read them in the story.

Zip, the alien, zaps a bot. Zip demands his bot to make him some hot mint tea. Instead the bot throws a pie in his eye. "'I see it fly into my eye.' Oh, my." Natalia confidently remarked in her cute 5 ½ year old voice, "Little rhyming words," and then giggled when she turned the page. Zip was mad. His anger backfires and multiplies the bots, each with a pie in hand! Hilarious! Finally, Zip zaps a tea and a pot and together they have a tea party.

|

| Poof! A Bot! by David Milgrim |

"Mint tea" slipped Natalia up at first (I thought for sure she would recognize the tea bag in the illustration since her mom is a tea drinker?) "Coffee? Hot chocolate?" Those were really the only words she had trouble with.

"I like the illustrations, especially the baby alien," she said pointing at the page. "And the pie in the eye was funny," she said laughing. "There really wasn't anything I didn't like."

It's no wonder that David Milgrim has won two Geisel honors. He has a knack for writing exciting, funny, page turners for our newest readers. And even though Natalia rated both books 4 ½ stars out of 5 (Does giving a half sound grown up?), I would easily zap these books to the top of any Geisel contending list. Go, David, go!

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Holiday House Spring 2019 Titles

|

| Photo of Jamie Chowning. Courtesy of Jamie Chowning |

Holiday House added three new titles in the beginning reader category during the first half of this year: one standalone title with slightly different packaging and two entries for its I Like to Read series, with Fountas & Pinnell levels. On the whole, these are weaker offerings than those of the last year or two (Take a look back at Fall 2017, Spring 2018, and Fall 2018).

|

| I Like My Bike by AG Ferrari book cover |

I Like My Bike is the lowest reading level, at level A. As with all the very earliest readers, it repeats a phrase (in this case, “I like my”) and only the last word changes from page to page, supported by an illustration.

|

| Image of a blue limo with a shark inside from I Like My Bike by AG Ferrari |

While it is difficult to develop a plot with such a very limited vocabulary, the best readers at this level do manage to create a sense of sequence or even dramatic tension. The order here feels random. The original girl on a bicycle appears on every page, but there is no trajectory--she’s not going anywhere. The choice to repeat entire sentences (“I like my truck,” for instance, appears on two consecutive pages with different illustrations) also feels odd. Children will probably enjoy the novelty of the illustrations, such as what appear to be two pickles driving a flower truck. Most of the characters portrayed are animals, but there are a few people, one of whom is visibly a person of color.

As a librarian, I wouldn’t hesitate to send this one home with a kindergartner or a preschooler who’s just getting started with reading--but first I would look to see if the stronger level A readers from this series were on the shelf.

|

| I Dig by Joe Cepeda book cover |

On the other hand, I would hesitate to recommend I Dig. Digging sand tunnels is very dangerous (you can read more here and here)! While the book doesn’t seem to be intended as realistic, I am troubled by normalizing a traditional but potentially deadly activity.

|

| Image of a child and a dog crawling through a sand tunnel from I Dig by Joe Cepeda |

Another concern with I Dig is the awkward sentences. Some awkwardness is probably inevitable in books for very early readers, but this one stuck out as more stilted than most, with “Look” on three consecutive pages and pages reading “I go” and “He is up,” which are simply not natural. Taken together, that’s a fairly high percentage of the pages that just seem “off.”

|

| I Am Just Right by David McPhail book cover |

While prolific author David McPhail has several entries in the I Like To Read series already, Holiday House chose to publish I Am Just Right as a standalone title. Although also for very young readers, it is more complex than the leveled ILTR readers while still being strongly supportive. Heavy repetition early in the book lets kids get comfortable and feel confident before they tackle more difficult later pages. Along with some longer sentences, these include repeated practice of the hard-to-learn sight word “right.”

|

| Image of a young bunny being picked up and hugged by a grandpa bunny from I Am Just Right by David McPhail |

The story is sweet and simple as a bunny explores beloved items he has outgrown as well as those for which he is “just right.” (Although the bunny is not referred to by any personal pronouns, in the illustrations he presents as male.) Young readers are likely to identify with the bittersweetness of outgrowing things--especially being picked up--and learning to accept a new, bigger place in the world. Though not an exciting tale, it has enough “kid appeal” that I can see it working as a bedtime story for a child and caregiver to share.

These are individually and collectively “just okay.” Unfortunately, the awkwardness of the first two titles may not invite repeated readings, and the strongest offering isn’t even included in the series. At my library, all the ILTR titles are shelved together, so I Am Just Right will be shelved separately and I might not think of reaching for it. I keep hoping that Holiday House will match its success of fall 2017, when it released almost a full slate of engaging, supportive titles, and I was on the whole disappointed in this batch.

Monday, August 12, 2019

Bunny Will Not Smile! and Kiwi Cannot Reach! by Jason Tharp

Today's guest contributor, Anna Taylor, is the Head of Youth Services for Darien Library in CT. She currently serves on ALCT's Cataloging of Children's Materials Committee and is active in ALSC and YALSA.

Bunny Will Not Smile!

Written and illustrated by Jason Tharp

Two characters, Bunny and Bear, star in this “Ready-to-Read Level 1” book. Blue Bear immediately breaks the fourth wall by asking readers if they can help him with a big problem. We find out the big problem is purple Bunny will not smile. With help from the reader, Bear is able to make Bunny smile.

Playing on the graphic novel trend in picture books, Bunny and Bear talk in color-coordinated speech bubbles (i.e. Bunny is purple and has purple speech bubbles). The limited color palette of primarily purple and blue helps focus the story on the text, and the pops of color that come in help with text clues.

All of the font in the story is the same size, color, and format. The only time the font is different is on the cover of the book and title page.

Kiwi Cannot Reach!

Written and illustrated by Jason Tharp

In this early reader book we meet one character called Kiwi, who is a kiwi bird. While also a “Ready-to-Read Level 1” book, Kiwi uses more text, colors, and illustrations to have readers help Kiwi pull an overhead rope. Readers brainstorm with Kiwi to figure out how to reach the rope hanging far above their head.

Kiwi also uses graphic novel bubbles but incorporates them for both speech and thought. Unlike Bunny, Kiwi has various font sizes to emphasize words as well as sound effect using various text colors, sizes, and font. While Bunny focused more on the text and some visual cues, Kiwi relies more on visual cues to problem-solve. At times there is more than one thing happening on a page, cluttering the small trim size.

Conclusion:

Both books serve as good read aloud for young readers, however, when it comes to the purpose of a learning to read tool, one is superior. Bunny Will Not Smile hits everything on the head. Fun characters, easy-to-read text and words, entertaining story, and readability. I believe it is a contender for the Geisel Award.

|

| Image from Simon & Schuster website |

Written and illustrated by Jason Tharp

Two characters, Bunny and Bear, star in this “Ready-to-Read Level 1” book. Blue Bear immediately breaks the fourth wall by asking readers if they can help him with a big problem. We find out the big problem is purple Bunny will not smile. With help from the reader, Bear is able to make Bunny smile.

Playing on the graphic novel trend in picture books, Bunny and Bear talk in color-coordinated speech bubbles (i.e. Bunny is purple and has purple speech bubbles). The limited color palette of primarily purple and blue helps focus the story on the text, and the pops of color that come in help with text clues.

|

| Image from Simon & Schuster website |

All of the font in the story is the same size, color, and format. The only time the font is different is on the cover of the book and title page.

|

| Image from Simon & Schuster website |

Kiwi Cannot Reach!

Written and illustrated by Jason Tharp

In this early reader book we meet one character called Kiwi, who is a kiwi bird. While also a “Ready-to-Read Level 1” book, Kiwi uses more text, colors, and illustrations to have readers help Kiwi pull an overhead rope. Readers brainstorm with Kiwi to figure out how to reach the rope hanging far above their head.

Kiwi also uses graphic novel bubbles but incorporates them for both speech and thought. Unlike Bunny, Kiwi has various font sizes to emphasize words as well as sound effect using various text colors, sizes, and font. While Bunny focused more on the text and some visual cues, Kiwi relies more on visual cues to problem-solve. At times there is more than one thing happening on a page, cluttering the small trim size.

|

| Image from Simon & Schuster website |

Both books serve as good read aloud for young readers, however, when it comes to the purpose of a learning to read tool, one is superior. Bunny Will Not Smile hits everything on the head. Fun characters, easy-to-read text and words, entertaining story, and readability. I believe it is a contender for the Geisel Award.

Friday, August 9, 2019

Flubby Is Not a Good Pet and Flubby Will Not Play with That, written and illustrated by J. E. Morris

Today's post comes from Jackie Partch. Jackie is a School Corps Librarian at Multnomah County Library, where she does outreach to K-12 students. She was a member of the 2012 Geisel committee.

Kami and her cat Flubby star in these two titles. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, Kami notices that all her friends' pets have special talents (i.e.: singing, jumping, playing catch), and she wonders what Flubby's special ability might be. Meanwhile, in Flubby Will Not Play with That, Flubby stubbornly refuses to play with any of the toys Kami bought at the pet store. Let's see how these books could be evaluated using some of the Geisel criteria:

Subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read; The plot advances from one page to the next, and together with the illustrations, creates a "page-turning" dynamic

Pets (and their talents) always a popular topic for young readers, and Flubby's repeated failure to meet Kami's expectations will keep them turning the pages to see what Flubby can do (spoiler alert: he manages to please her at the end of both stories). The cat's actions and expressions add lots of visual humor, too.

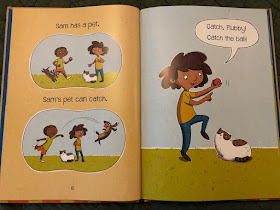

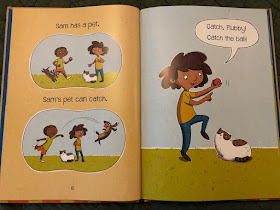

New words should be added slowly enough to make learning them a positive experience;

Words should be repeated to ensure knowledge retention

Both books excel in this area. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, one new word is added as each of Kami's friends arrives, and that same word is repeated several times over the next few pages (see photo). In Flubby Will Not Play with That, words follow a pattern each time Kami tries (unsuccessfully) to get Flubby to play with a toy, always ending with, "It is fine. I have another toy."

Both books excel in this area. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, one new word is added as each of Kami's friends arrives, and that same word is repeated several times over the next few pages (see photo). In Flubby Will Not Play with That, words follow a pattern each time Kami tries (unsuccessfully) to get Flubby to play with a toy, always ending with, "It is fine. I have another toy."

Sentences must be simple and straightforward;

This is also a strength; most sentences are only 3-4 words long and fit on one line.

The book must also contain illustrations, which function as keys or clues to the text

Both books have a mix of full page illustrations and easy-to-follow panels. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, the illustrations make excellent clues; as new words are introduced, they are almost always pictured. Generally this is also the true in Flubby Will Not Play with That, but there are a few cases where text placement could work better. For example, on page 11, the text reads, "This toy rolls," but the action of rolling does not occur in the illustrations until page 12, after the reader has turned the page.

The design of the book includes attention to size of typeface, an uncluttered background that sets off the text, appropriate line length, and placement of illustrations

The typeface is large, in a sans serif font, and is easy to read. Words are sometimes smaller in speech bubbles and sound effects, although those are not necessary to read to understand the plot. Text is sometimes placed over the illustrations, but always in an uncluttered area.

The book shows excellent, engaging and distinctive use of both language and illustration

I always find this criteria a difficult one to judge until I'm comparing books. I enjoyed both of these books, and I think beginning readers will, too. Will the committee decide that they are "excellent, engaging and distinctive?" Leave a comment with your ideas.

Kami and her cat Flubby star in these two titles. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, Kami notices that all her friends' pets have special talents (i.e.: singing, jumping, playing catch), and she wonders what Flubby's special ability might be. Meanwhile, in Flubby Will Not Play with That, Flubby stubbornly refuses to play with any of the toys Kami bought at the pet store. Let's see how these books could be evaluated using some of the Geisel criteria:

Subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read; The plot advances from one page to the next, and together with the illustrations, creates a "page-turning" dynamic

Pets (and their talents) always a popular topic for young readers, and Flubby's repeated failure to meet Kami's expectations will keep them turning the pages to see what Flubby can do (spoiler alert: he manages to please her at the end of both stories). The cat's actions and expressions add lots of visual humor, too.

New words should be added slowly enough to make learning them a positive experience;

Words should be repeated to ensure knowledge retention

Both books excel in this area. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, one new word is added as each of Kami's friends arrives, and that same word is repeated several times over the next few pages (see photo). In Flubby Will Not Play with That, words follow a pattern each time Kami tries (unsuccessfully) to get Flubby to play with a toy, always ending with, "It is fine. I have another toy."

Both books excel in this area. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, one new word is added as each of Kami's friends arrives, and that same word is repeated several times over the next few pages (see photo). In Flubby Will Not Play with That, words follow a pattern each time Kami tries (unsuccessfully) to get Flubby to play with a toy, always ending with, "It is fine. I have another toy."Sentences must be simple and straightforward;

This is also a strength; most sentences are only 3-4 words long and fit on one line.

The book must also contain illustrations, which function as keys or clues to the text

Both books have a mix of full page illustrations and easy-to-follow panels. In Flubby Is Not a Good Pet, the illustrations make excellent clues; as new words are introduced, they are almost always pictured. Generally this is also the true in Flubby Will Not Play with That, but there are a few cases where text placement could work better. For example, on page 11, the text reads, "This toy rolls," but the action of rolling does not occur in the illustrations until page 12, after the reader has turned the page.

The design of the book includes attention to size of typeface, an uncluttered background that sets off the text, appropriate line length, and placement of illustrations

The typeface is large, in a sans serif font, and is easy to read. Words are sometimes smaller in speech bubbles and sound effects, although those are not necessary to read to understand the plot. Text is sometimes placed over the illustrations, but always in an uncluttered area.

The book shows excellent, engaging and distinctive use of both language and illustration

I always find this criteria a difficult one to judge until I'm comparing books. I enjoyed both of these books, and I think beginning readers will, too. Will the committee decide that they are "excellent, engaging and distinctive?" Leave a comment with your ideas.

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

Garden Day! by Candice Ransom, Illustrated by Erika Meza

|

| Garden Day! by Candice Ransom, illustrated by Erika Meza book cover |

You might recognize this family. They’ve been featured in other seasonally relevant Step into Reading titles by Ransom and Meza, including Snow Day!, Apple Picking Day!, Garden Day!, and Pumpkin Day! As with other titles in this series, the large font and ample white space are excellent.

Let’s take a look at the words. Most words are single syllable, with just a few double syllable words thrown in (scarecrow, hungry, buzzing). There’s also the rhyming text to consider. Rhyming may help some readers predict the final word in a sentence, however the lack of word repetition may hinder readers by introducing too many new words without adequate support.

|

| Image from Garden Day! by Candice Ransom, illustrated by Erika Meza |

|

| Image from Garden Day! by Candice Ransom, illustrated by Erika Meza |

The through-line of the story -- planting and tending a garden -- holds up well until the penultimate page turn. Suddenly, the family is at a farm stand. Without any foreshadowing or relevance to the plot line, this abrupt change in location is quite jarring.

|

| Image from Garden Day! by Candice Ransom, illustrated by Erika Meza |

Monday, August 5, 2019

We Are (Not) Friends by Anna Kang, Illustrated by Christopher Weyant

|

| Photo courtesy of Robbin Friedman |

|

| We Are (Not) Friends by Anna Kang, illustrated by Christopher Weyant book cover |

Geisel Award-winning team Anna Kang and Christopher Weyant return with another fuzzy monster book, the third companion to You Are (Not) Small. After the crystalline simplicity of the winning first title, We Are (Not) Friends broaches slightly more complicated territory, in both emotional and literary content.

The early reading foundations of Kang and Weyant’s work remain the same. The story unfolds as dialogue between three characters, mostly printed in a large, well-spaced serif typeface. Jaunty lines connect the speaker to each instance of dialogue; sound effects and a few shouts appear in a legible, handwritten typeface. Variations in font size, occasional italics, and underlined words guide the reader’s emotional expression, while remaining comprehensible.

|

| Image from We Are (Not) Friends by Anna Kang, illustrated by Christopher Weyant |

Still, We Are (Not) Friends introduces a layer of difficulty beyond the earlier text. The story examines the challenges--emotional and logistical--that come from bringing new friends into an existing relationship. Over the course of the narrative, alliances shift and the two original friends each experience feeling slighted and jealous before settling into a happy trio. This story of friendship, kindness, and hurt feelings will resonate with most beginning readers, who may also be beginners at cultivating relationships and reacting to other people’s emotions. But the dynamics reverse quickly, and readers new to decoding text will also have to decode the illustrations to understand when the three creatures feel excluded, or sad, or excited. The open faces and expressive body language, set against uncluttered backgrounds, offer readers ample clues to the characters’ emotions, but readers will still need to know what to do with that information.

|

| Image from We Are (Not) Friends by Anna Kang, illustrated by Christopher Weyant |

As with the earlier texts, Kang keeps the sentences short, employing sight words and repetition. But not every vocabulary word gets enough support and in one case, it may affect the reader’s experience. Early on in the book, newcomer Blue hands Yellow a cane (a la Fred Astaire) and suggests “We can do a duet.” This two-person activity, proposed while all three characters are together, sets the stage for the jealousy and exclusion that come next. But will beginning readers recognize the word “duet” (or know how to pronounce it)? Will they identify that it separates two characters from the third? The illustrations pull a lot of weight on the following spread, depicting Purple’s growing discontent at being left out. But the book never returns to the crucial piece of vocabulary, so readers likely won’t have understood the new term in context, or learn it for the future. Other terms--two-seater, dinosaur, attack--fall well outside any standard sight-word list.

As a relatable saga, We Are (Not) Friends pairs tension and humor, a great combination to induce Geisel-criteria page-turning to the very end. And the final turn (familiar to readers of Chester’s Way, among others) will satisfy most readers. People looking for age-appropriate tales of navigating friendship will find this book charming, funny, and emotionally astute. But the Geisel Committee, looking for scaffolding and success, probably won’t call for an encore.