Today's guest contributor is Elisa Gall. Elisa is the Director of Library Services at an independent school in Chicago serving children in preschool through high school. Find her on Twitter @gallbrary.

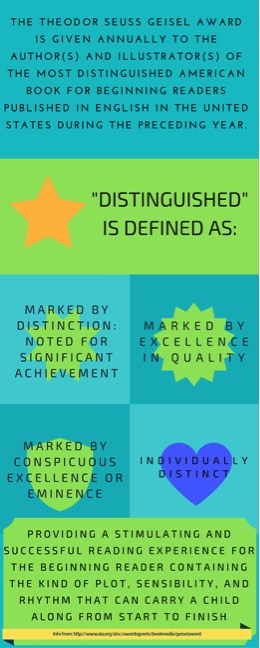

I’ve been thinking about the word "distinguished" lately. It is no stranger to ALSC award language, and no matter how much the association goes out of its way to define it (see graphic) it can still seem ambiguous. One person’s perceived flaw for a book can be that same thing which makes a book "individually distinct" to another committee member. But it is true (to me at least) that a book cannot be a serious contender for the award if it does not fit all the elements of the "distinguished" definition.

In Pug by Ethan Long, readers follow a wide-eyed pug (named "Pug") as it looks pleadingly out the window at "Peg" on a snowy day. When Pug sees Peg, readers see a bundled-up girl walking through the neighborhood. Pug yaps at each member of its family (with leash nearby) to hint that it would like to be outside. Only when Tad, the kid of the family, fears that Pug will have an accident on his bed does he reluctantly leave the cozy house to fulfill Pug’s request. When Tad and Pug meet Peg, it is revealed that Peg is the pet pug of the girl who has been walking through the snow, and not the girl readers have seen (and who Tad later befriends).

Using twelve unique words, Long presents an engaging and accessible story. Sentences average three words each, and the polished digital illustrations are full of bold lines that appropriately match the text’s large, clear font. Words and images work in tandem, but readers must make some inferences. When the dogs communicate through yaps, for example, the sounds are color coded to represent which animal is barking. Readers even see Peg’s yaps when she is not shown on the page. (Pug’s ear is in the air to show that the noises are coming from somewhere unseen.) As words are repeated, they take on deeper meaning too. For example, after Pug lifts its back leg into the air (and Tad says, "No, Pug, No.") readers turn the page and see Tad and Pug outside, with the words "Go, Pug, go." accompanying them. The "go" on this page can mean Pug is going outside, but there is another (more humorous) type of "go" that it can also represent.

Some critics might argue that it might be confusing for an emergent reader to see Peg revealed as a dog (and not the girl previously shown) in the story’s surprise ending. They might point to the part of the Geisel criteria that states, "illustrations must demonstrate the story being told." I would ask someone with these concerns to consider how that final revelation does tell the story—through images. I would ask them to think about how many works of visual narrative use complicated and in some cases contradictory images and words to tell their stories. Pug is a beginning reader for children who are learning to read a book’s text, pictures, and everything in between. It is a reader for both traditional literacy and visual literacy. To me, that makes it "individually distinct" and worthy of the debatable "distinguished" category. What do you all think?

Pages

▼

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Sunday, August 21, 2016

#WeNeedDiverseBeginningReaders

This week's contributor is Gigi Pagliarulo, a librarian for the Denver Public Library. Gigi is especially interested in youth services, early literacy, and issues of diversity and multiculturalism within children's literature and programming, and has served on the steering committee of Colorado Libraries for Early Literacy.

It’s time for a short but important digression from our regularly scheduled mocking. I’m here today to talk to you about diversity in children’s literature and publishing, and to promote this idea:

#WeNeedDiverseBeginningReaders!

In 2014, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign was formed to create dialogue and action around the pervasive and endemic dearth of diversity in the children’s book publishing industry. In the short time since its inception, #WeNeedDiverseBooks has accomplished an enormous amount. Most importantly, they have spearheaded noticeable, significant change in publishing trends, book convention panels, and many of the recent major children’s book award winners. Today the organization hands out awards and grants, provides author and illustrator mentorships, holds writing symposiums, assembles roundtable forums, creates resources and booklists, mobilizes awareness and publicity campaigns, and champions issues of diversity in children’s literature and publishing across multiple digital forums.

The statistics on children’s book publishing and diversity, as I’m sure you’ve heard, aren’t very pretty. Annual reports on diversity in children’s publishing from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center display dismal trends and scant improvement over the last decade when considering books by and about African/African Americans, American Indians/First Nations, Asian Pacifics/Asian Pacific Americans, and Latinos. Of the 3400 books received by the CCBC in 2015, only 10.6% of them were by and 14.8% were about people of color and First/Native Nations. To make matters worse, many characters in children’s books are animals, rather than people, knocking the number of reflective images kids see in books down another notch. Kathleen Horning, director of the CCBC, informally estimates that in any given year, less than 10% of picture book protagonists are people of color.

With a vision of a world where all children can see themselves in the pages of a book and a mission to put more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children, #WeNeedDiverseBooks has outlined 7 essential benefits to reading diverse books. These are benefits shared by children of color and white children alike.

So where do traditional (and nontraditional) beginning readers fit in to all of this? They certainly aren’t the darlings of the children’s publishing industry, and they usually aren’t the flashiest kids on the block. They only got their own award 10 years ago. And yet, while they are but a short part of a child’s lifelong reading diet, they serve a vital purpose. As Kathleen Horning (her again, that smart lady!) says in Cover to Cover, her seminal guide to children’s literature, “It is during this stage that the child gains confidence and discovers that reading is personally important and pleasurable” (2010, p 132). Thus, if we want the social and educational benefits of diversity in children’s literature to become a foundational element of children’s experiences of reading as enjoyable and worthwhile, we need high quality books written specifically for children who learning to read… #WeNeedDiverseBeginningReaders!

With all of this in mind, here is a small starting point, with some suggestions for read-alikes that pair Geisel award-winning titles with high-quality, culturally diverse beginning readers.

It’s time for a short but important digression from our regularly scheduled mocking. I’m here today to talk to you about diversity in children’s literature and publishing, and to promote this idea:

#WeNeedDiverseBeginningReaders!

In 2014, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign was formed to create dialogue and action around the pervasive and endemic dearth of diversity in the children’s book publishing industry. In the short time since its inception, #WeNeedDiverseBooks has accomplished an enormous amount. Most importantly, they have spearheaded noticeable, significant change in publishing trends, book convention panels, and many of the recent major children’s book award winners. Today the organization hands out awards and grants, provides author and illustrator mentorships, holds writing symposiums, assembles roundtable forums, creates resources and booklists, mobilizes awareness and publicity campaigns, and champions issues of diversity in children’s literature and publishing across multiple digital forums.

The statistics on children’s book publishing and diversity, as I’m sure you’ve heard, aren’t very pretty. Annual reports on diversity in children’s publishing from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center display dismal trends and scant improvement over the last decade when considering books by and about African/African Americans, American Indians/First Nations, Asian Pacifics/Asian Pacific Americans, and Latinos. Of the 3400 books received by the CCBC in 2015, only 10.6% of them were by and 14.8% were about people of color and First/Native Nations. To make matters worse, many characters in children’s books are animals, rather than people, knocking the number of reflective images kids see in books down another notch. Kathleen Horning, director of the CCBC, informally estimates that in any given year, less than 10% of picture book protagonists are people of color.

With a vision of a world where all children can see themselves in the pages of a book and a mission to put more books featuring diverse characters into the hands of all children, #WeNeedDiverseBooks has outlined 7 essential benefits to reading diverse books. These are benefits shared by children of color and white children alike.

- They reflect the world and people of the world

- They teach respect for all cultural groups

- They serve as a window and a mirror and as an example of how to interact in the world

- They show that despite differences, all people share common feelings and aspirations

- They can create a wider curiosity for the world

- They prepare children for the real world

- They enrich educational experiences (Source here)

So where do traditional (and nontraditional) beginning readers fit in to all of this? They certainly aren’t the darlings of the children’s publishing industry, and they usually aren’t the flashiest kids on the block. They only got their own award 10 years ago. And yet, while they are but a short part of a child’s lifelong reading diet, they serve a vital purpose. As Kathleen Horning (her again, that smart lady!) says in Cover to Cover, her seminal guide to children’s literature, “It is during this stage that the child gains confidence and discovers that reading is personally important and pleasurable” (2010, p 132). Thus, if we want the social and educational benefits of diversity in children’s literature to become a foundational element of children’s experiences of reading as enjoyable and worthwhile, we need high quality books written specifically for children who learning to read… #WeNeedDiverseBeginningReaders!

With all of this in mind, here is a small starting point, with some suggestions for read-alikes that pair Geisel award-winning titles with high-quality, culturally diverse beginning readers.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

Classic Beginning Readers: Useful? Relevant?

Today's guest contributor is Carol Edwards. After many years as a youth services librarian, Carol currently works as the Project Coordinator for SPELL; Supporting Parents in Early Literacy through Libraries. She has a granddaughter just starting first grade who is a real reader and has been reminding her of the way learning to read is both a challenge and very rewarding. Carol has served on the Newbery, Caldecott, Morris, and Coretta Scott King Award committees as well as being involved in CLEL, Colorado Libraries for Early Literacy and their CLEL BELL Awards.

The classic books for early readers that are still around exemplify the needs of beginning readers. These readers struggle to look at the black ink marks on the page and turn those into first words, then ideas and stories in their heads. I’ve looked back at a number of titles that charmed and delighted those just learning to read long before the Geisel Award was instituted in 2006. While Dr. Seuss is the obvious name to mention, I thought I would not focus on his work this time, but on others who were, I think, just as influential in developing the standards that have been handed down.

One thing is clear. The subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read and the story move along quickly. A Kiss for Little Bear by Else Holmelund Minarik (1968) is a favorite. Things happen from page to page, and always the pictures provide clues to the decoding required. I just love the memorable phrases, such as "Too much kissing" [p.21]. A satisfying story with a beginning, middle and end.

Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books are classics that everyone knows. Frog and Toad are good friends, and the books about them evoke many of the best qualities of early readers today. Frog and Toad are both not nearly as clever as the average kid learning to read. Doesn't this remind you of Gerald and Piggie? This ability for the reader to feel superior and to laugh at their antics is a quality that Lobel showcased in Owl at Home (1975) as well. There are places in them to pause and consider the motivation and thoughts of the characters. This allows the reader to both focus on what is being read and to consider it at a slow pace that is commensurate with their reading ability. Since these books are often read with a better reader nearby, whether grownup or older child, the humor is bound to connect the two readers, making the reading seem cooperative rather than competitive.

Helen Palmer, who wrote A Fish out of Water, was married to Ted Geisel until her death in 1967, and adapted this book from a short story of his. The lovely repetition and the increasingly unbelievable results are reminiscent of other Dr. Seuss titles, but this book has its own charm as the conclusion returns the reader to normalcy. The flow between pictures and words works very well, providing cues and laughter simultaneously. Personally, this story always resonated with me, as I have distinct memories of being told not to feed the fish too much fish food. There are probably many kids who have wondered what would happen, although the fish usually die as mine did. A sad ending deftly avoided here.

Robert Lopshire wrote Put Me in the Zoo (1960), and it's certainly showing its age, particularly in the illustrations. However it continues to serve young readers. Not full of plot, but an engaging stroll with a strange creature sharing his odd powers. He speaks directly to both a young girl and boy, and to the reader. It's an early example of how engaging the reader as a participant can pay off.

Johnny Lion's Book (1965) shows the reader how the story in a book can be as exciting as doing those things in the real world, but not nearly as dangerous. Johnny's good behavior is rewarded by being able to stay up "very, very late." p.59. A reward indeed -- as every book you read should be.

Classic early readers show us that repetition and simple vocabulary are not all that is needed. We need stories that are appealing, that both move along quickly and allow the reader time to absorb the meaning of the words. Illustrations play a key role, and there is obviously no one right way to do it, but a light touch is certainly appreciated.

The classic books for early readers that are still around exemplify the needs of beginning readers. These readers struggle to look at the black ink marks on the page and turn those into first words, then ideas and stories in their heads. I’ve looked back at a number of titles that charmed and delighted those just learning to read long before the Geisel Award was instituted in 2006. While Dr. Seuss is the obvious name to mention, I thought I would not focus on his work this time, but on others who were, I think, just as influential in developing the standards that have been handed down.

One thing is clear. The subject matter must be intriguing enough to motivate the child to read and the story move along quickly. A Kiss for Little Bear by Else Holmelund Minarik (1968) is a favorite. Things happen from page to page, and always the pictures provide clues to the decoding required. I just love the memorable phrases, such as "Too much kissing" [p.21]. A satisfying story with a beginning, middle and end.

Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad books are classics that everyone knows. Frog and Toad are good friends, and the books about them evoke many of the best qualities of early readers today. Frog and Toad are both not nearly as clever as the average kid learning to read. Doesn't this remind you of Gerald and Piggie? This ability for the reader to feel superior and to laugh at their antics is a quality that Lobel showcased in Owl at Home (1975) as well. There are places in them to pause and consider the motivation and thoughts of the characters. This allows the reader to both focus on what is being read and to consider it at a slow pace that is commensurate with their reading ability. Since these books are often read with a better reader nearby, whether grownup or older child, the humor is bound to connect the two readers, making the reading seem cooperative rather than competitive.

Helen Palmer, who wrote A Fish out of Water, was married to Ted Geisel until her death in 1967, and adapted this book from a short story of his. The lovely repetition and the increasingly unbelievable results are reminiscent of other Dr. Seuss titles, but this book has its own charm as the conclusion returns the reader to normalcy. The flow between pictures and words works very well, providing cues and laughter simultaneously. Personally, this story always resonated with me, as I have distinct memories of being told not to feed the fish too much fish food. There are probably many kids who have wondered what would happen, although the fish usually die as mine did. A sad ending deftly avoided here.

Robert Lopshire wrote Put Me in the Zoo (1960), and it's certainly showing its age, particularly in the illustrations. However it continues to serve young readers. Not full of plot, but an engaging stroll with a strange creature sharing his odd powers. He speaks directly to both a young girl and boy, and to the reader. It's an early example of how engaging the reader as a participant can pay off.

Johnny Lion's Book (1965) shows the reader how the story in a book can be as exciting as doing those things in the real world, but not nearly as dangerous. Johnny's good behavior is rewarded by being able to stay up "very, very late." p.59. A reward indeed -- as every book you read should be.

Classic early readers show us that repetition and simple vocabulary are not all that is needed. We need stories that are appealing, that both move along quickly and allow the reader time to absorb the meaning of the words. Illustrations play a key role, and there is obviously no one right way to do it, but a light touch is certainly appreciated.

Friday, August 5, 2016

Not Me! By Valeri Gorbachev

Today's guest contributor, Robbin Friedman, is a children's librarian at the Chappaqua Library. She chairs ALSC's School Age Programs and Service committee, serves on the Carnegie Medal/Notable Children's Videos committee, and writes reviews and other what-have-you for School Library Journal.

In 2013, Valeri Gorbachev’s Me Too! debuted Bear and Chipmunk, friends of unequal size but matching enthusiasm for wintry fun. Now experiencing a heat wave (with which we can all sympathize), the pair take a trip to the beach in Not Me! This time around, Bear describes his excitement about the seaside: “‘I like the sun,” said Bear.” “”I hope we see a big fish,’ said Bear.” Chipmunk, however, does NOT enjoy the sand and surf and responds to Bear’s eagerness with a refrain of “Not me!” until the two friends finally head home at the end of the day.

|

| Image from holidayhouse.com |

As we have come to expect from Holiday House’s I Like to Read series, the book features a non-serif font of an ample size, effective line breaks and a large enough format to enjoy the lively illustrations. But does it propel burgeoning readers to turn pages? While the text’s comfortable rhythm and the spirited pictures offer much to appreciate on each spread, the book operates without a sense of suspense or an obvious narrative arc and may not drive readers to stay through to the end. Readers who do will be rewarded with a friendly resolution in the animals’ final exchange and a clever, but simple, inversion of the title phrase. When Bear eventually asks beach-resistant Chipmunk why he came, the rodent answers that he wanted to be with Bear. “‘You are a good friend,’ said Bear. ‘That’s me!’ said Chipmunk.” Fans of sweet friendships, fun-filled illustrations and beachy reads will likely find many elements to enjoy in this story. But without the “page-turning dynamic” from the award’s criteria, I suspect that this year’s Geisel Committee will decide the book is not quite for them.